It goes without saying that substitute teachers are crucial in schools. By the time students graduate high school, they have spent about 8% of their school time with substitute teachers according to a 2000 estimate.

Yet, we seldom hear about substitutes’ experiences.

As such, Australian researchers reviewed 29 studies, mainly from the U.S. and Australia to learn more. They found that while substitutes’ classroom experiences are similar worldwide, there’s a notable difference in qualifications. In the U.S., some substitutes don’t need a teaching license or even a bachelor’s degree, unlike in Australia.

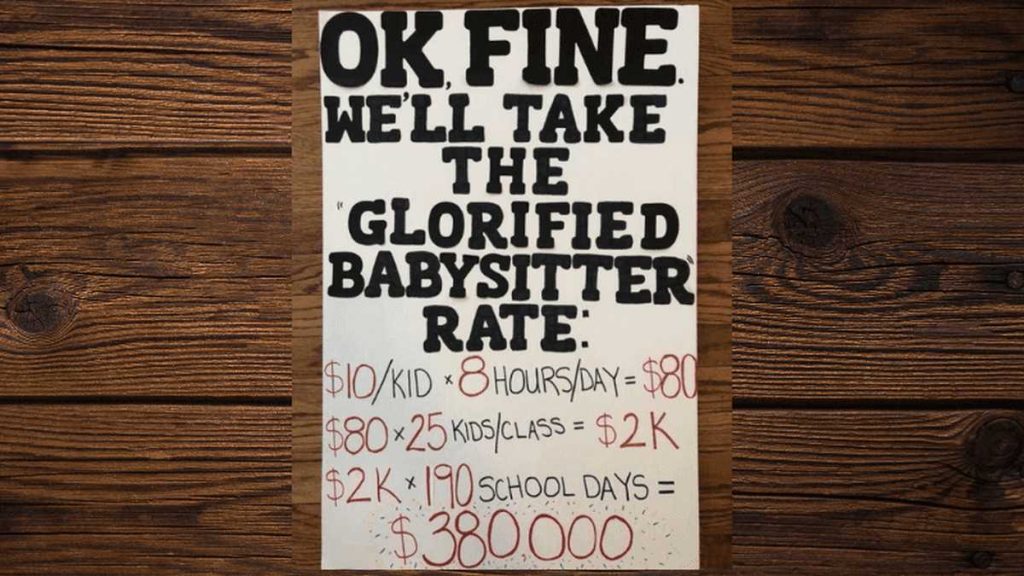

Andrea Reupert, an educational psychology professor at Monash University, was struck by this, noting it reduces the perception of substitutes to mere babysitters. The U.S. has recently relaxed substitute teaching standards due to teacher shortages.

However, Reupert suggests the shortage of substitutes might also be due to the challenging nature of the job.

The Sad Reality Behind Being a Substitute Teacher

Substitute teachers also desire a supportive and respectful work environment. However, they often feel marginalized, especially in schools they’re not familiar with.

Due to this, they tend to experience disconnection from the school community and feel treated as outsiders.

Reupert notes many substitutes find staff rooms unwelcoming, leading some to eat lunch in their cars. Even though administrators say substitutes are welcome in planning and training sessions, these invitations often don’t feel genuine, and substitutes rarely participate.

Substitutes also hesitate to ask questions, fearing they might burden regular staff or appear unprofessional.

This creates a gap between the ideal and actual experiences of substitute teachers in schools.

Oftentimes, substitute teachers feel less respected by students compared to permanent teachers and struggle to build relationships with them. Andrea Reupert points out that this lack of respect is influenced by how the school community treats substitutes, shaping students’ attitudes.

However, the research shows a positive trend with experience. Experienced substitutes become more adept at classroom management and adapting to different environments, and they are more likely to feel part of the school community.

This suggests that as substitutes gain familiarity and experience, their integration and acceptance within schools improve.

How the Substitute Teaching Model Might Be Improved

In the U.S., for example, some districts have started using full-time substitutes who work at a single school rather than drawing from a pool of substitutes who move between schools. Andrea Reupert notes this approach addresses many issues identified in the research.

For one, it allows substitutes to become familiar with the school, including logistical details and professional development opportunities. This makes them an integrated part of the school community.

However, this model is more common in wealthier areas, while lower socioeconomic areas, facing greater challenges, often can’t afford full-time substitutes. This discrepancy exacerbates existing inequities.

Reupert advocates for more research on effective professional development tailored to different kinds of substitutes, such as retired teachers versus those early in their careers. She also emphasizes the importance of hearing directly from substitutes, as their experiences often differ from the perceptions of permanent staff.

Despite offers of professional development, many substitutes still feel disconnected.

Addressing the needs of substitute teachers is a long-term issue. Reupert stresses the importance of treating them professionally and with respect, which includes fair pay and development opportunities.

This is crucial for the benefit of students, as the frequency with which they interact with substitutes means they need more than just babysitters.